The story of the Steller's sea cow is one of the most tragic tales in the history of human-driven extinction. Discovered in 1741 by the naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller during Vitus Bering's ill-fated expedition, this massive marine mammal inhabited the cold waters of the Bering Sea. Within just 27 years of its discovery by Europeans, the species was hunted to extinction—a stark reminder of humanity's capacity to irreversibly alter ecosystems.

The Steller's sea cow was a colossal creature, reaching lengths of up to 30 feet and weighing as much as 10 tons. Unlike its smaller relatives, the dugongs and manatees, it was uniquely adapted to the frigid Arctic environment. Its blubber, thick hide, and slow-moving nature made it an easy target for hunters seeking meat and fat. The sea cows were docile, social animals, often found in small family groups grazing on kelp beds—a behavior that sealed their fate once humans arrived in their habitat.

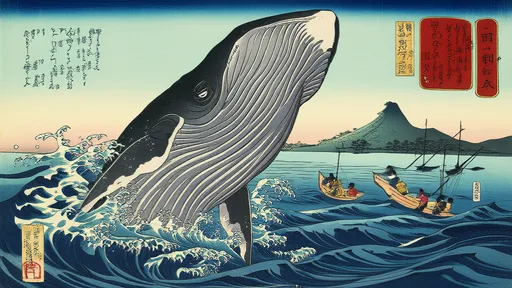

What makes the extinction particularly alarming is the breathtaking speed at which it occurred. From the moment Russian fur traders and explorers learned of the sea cow's existence, the species was relentlessly pursued. The animals were harpooned from boats, their populations decimated not just for sustenance but also to supply ships with provisions for long voyages. By 1768, the last known Steller's sea cow was killed, marking the end of a species that had thrived for thousands of years in isolation.

The ecological impact of their disappearance was profound. As keystone herbivores, sea cows played a critical role in maintaining the health of kelp forests. Their grazing kept kelp growth in check, allowing sunlight to reach younger plants and fostering biodiversity. Without them, the underwater landscape of the Bering Sea changed dramatically, though the full extent of these changes remains a subject of scientific inquiry.

Today, the Steller's sea cow serves as a cautionary symbol in conservation circles. Its extinction underscores the vulnerability of slow-reproducing marine mammals to human exploitation. Unlike fish or smaller marine life, sea cows had a low reproductive rate, with females giving birth to a single calf after a long gestation period. This biological reality made recovery from overhunting impossible once their numbers dropped below a critical threshold.

Modern parallels to the sea cow's fate are unsettling. The vaquita porpoise, the North Atlantic right whale, and other marine species teeter on the brink of extinction due to human activities. While international protections and conservation efforts exist today, enforcement remains inconsistent, and habitat destruction continues unabated in many regions. The 27-year window between discovery and extinction should serve as a dire warning—one that humanity cannot afford to ignore.

Scientists now study the Steller's sea cow through skeletal remains and historical accounts, piecing together its biology and ecology. Genetic research has revealed surprising connections to other sirenians, while isotopic analysis of bones provides clues about their diet and migration patterns. These studies not only illuminate the past but also inform present-day conservation strategies for endangered marine mammals.

The legacy of the Steller's sea cow extends beyond its tragic end. It stands as one of the first documented cases of a large mammal being driven to extinction in the modern era, setting a precedent for countless species that would follow. Its story compels us to reflect on our relationship with the natural world—a relationship that must evolve from exploitation to stewardship if we are to prevent similar ecological catastrophes in the future.

As climate change alters Arctic ecosystems and human activity expands into previously untouched regions, the lessons from the sea cow's extinction grow ever more relevant. The Bering Sea, once home to these gentle giants, now faces new threats from industrial fishing, shipping routes, and oil exploration. Protecting what remains of its biodiversity requires acknowledging past mistakes and making conscious choices to prioritize long-term ecological health over short-term gain.

Perhaps the most haunting aspect of the Steller's sea cow's story is how preventable its extinction was. With even basic conservation measures—hunting limits, protected areas, or simply restraint—the species might have survived into the modern age. Instead, it exists only in museum specimens and fading historical records, a silent testament to what happens when humanity fails to recognize the value of life beyond immediate utility.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025