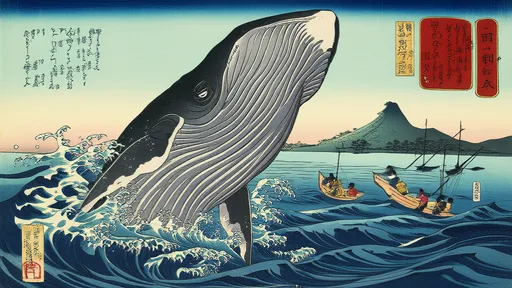

In the bustling streets of Edo-period Japan, where woodblock prints captured the essence of daily life, one motif emerged with surprising frequency: the whale. These colossal creatures of the deep, rendered in vivid blues and whites by ukiyo-e masters, were more than just artistic subjects—they were symbols of a complex relationship between humans and the untamable ocean. The whale prints of the 18th and 19th centuries reveal a cultural fascination that blended awe, fear, and pragmatic understanding of marine ecosystems long before Western whaling ships appeared on the horizon.

The Katsushika Hokusai school produced some of the most striking depictions, where whales often appear mid-breach, their barnacled bodies dwarfing fishing boats. What’s remarkable about these compositions is their tension between documentary precision and mythic grandeur. In "Off the Coast of Kazusa Province" (1832), Hokusai depicts a right whale with scientifically accurate baleen plates, yet positions it beneath a stormy vortex that echoes his famous "Great Wave". This wasn’t mere decoration—it reflected the very real peril fishermen faced when encountering these giants. Contemporary accounts describe boats being capsized by whale flukes, while other records tell of villages celebrating beached whales as "gifts from the sea god Ebisu".

Behind the artistry lay an intricate web of economic and spiritual significance. Coastal towns like Taiji and Ikitsuki had developed specialized whaling techniques using nets and harpoons by the 1670s—centuries before American whalers arrived. Ukiyo-e prints served as both news reports and propaganda; a successful hunt might be commemorated in a triptych, with the whale’s skeleton meticulously drawn to showcase the bounty. Yet parallel to this practical view existed a layer of Buddhist symbolism. The "Whale as Mountain" motif, seen in Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s works, presented whales as floating islands, their spines evoking sacred peaks. This duality captures Edo Japan’s worldview: the ocean was both pantry and temple, its creatures both resource and deity.

Scholars have noted how these prints functioned as ecological narratives. Unlike Western illustrations that isolated whales as specimens, Japanese artists consistently showed them in relationship—to humans, boats, and other sea life. A lesser-known print by Utagawa Hiroshige depicts a sperm whale surrounded by startled seabirds and fleeing fish, creating a snapshot of marine interdependence. Even graphic scenes of butchery often include shrine priests blessing the catch, acknowledging the spiritual cost of harvest. This holistic perspective may explain why Edo-period whaling maintained sustainable limits despite advanced techniques, while Western industrial whaling later caused catastrophic declines.

The decline of traditional whaling in the Meiji era coincided with the fading of whale ukiyo-e, but their legacy persists. Modern analyses using spectral imaging have revealed that the indigo pigments in these prints chemically match dyes from whale oil processing—a literal fusion of art and industry. Contemporary artists like Ayako Yoshikawa reinterpret these motifs to critique commercial whaling, proving the Edo aesthetic still carries moral weight. As climate change alters our oceans, these centuries-old prints remind us that human survival has always required balancing exploitation with reverence—a lesson as vital now as it was in the age of woodblocks and harpoons.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025